In Charles Stross’s novel The Atrocity Archive and its sequels, the “Laundry” is a secret British agency responsible for keeping dark interdimensional entitities from destroying the cosmos and, not incidentally, the human race. The battles with creatures from beyond time are dangerous; however, it’s the subsequent bureaucratic paperwork that actually breaks men’s souls. Now, in “Down on the Farm,” Laundry veteran Bob Howard must investigate strange doings at another obscure, moth-eaten government agency — evidently a rest home for Laundry agents whose minds have snapped…

“Down on the Farm” was acquired and edited for Tor.com by Patrick Nielsen Hayden.

Ah, the joy of summer: here in the south-east of England it’s the season of mosquitoes, sunburn, and water shortages. I’m a city boy, so you can add stifling pollution to the list as a million outwardly mobile families start their Chelsea tractors and race to their holiday camps. And that’s before we consider the hellish environs of the Tube (far more literally hellish than anyone realizes, unless they’ve looked at a Transport for London journey planner and recognized the recondite geometry underlying the superimposed sigils of the underground map).

But I digress…

One morning, my deputy head of department wanders into my office. It’s a cramped office, and I’m busy practicing my Frisbee throw with a stack of beer mats and a dart-board decorated with various cabinet ministers. “Bob,” Andy pauses to pluck a moist cardboard square out of the air as I sit up, guiltily: “a job’s just come up that you might like to look at—I think it’s right up your street.”

The first law of Bureaucracy is, show no curiosity outside your cubicle. It’s like the first rule of every army that’s ever bashed a square: never volunteer.

If you ask questions (or volunteer) it will be taken as a sign of inactivity, and the devil, in the person of your line manager (or your sergeant) will find a task for your idle hands. What’s more, you’d better believe it’ll be less appealing than whatever you were doing before (creatively idling, for instance), because inactivity is a crime against organization and must be punished. It goes double here in the Laundry, that branch of the British secret state tasked with defending the realm from the scum of the multiverse, using the tools of applied computational demonology: volunteer for the wrong job and you can end up with soul-sucking horrors from beyond spacetime using your brain for a midnight snack. But I don’t think I could get away with feigning overwork right now, and besides: he’s packaged it up as a mystery. Andy knows how to bait my hook, damn it.

“What kind of job?”

“There’s something odd going on down at the Funny Farm.” He gives a weird little chuckle. “The trouble is going to be telling whether it’s just the usual, or a more serious deviation. Normally I’d ask Boris to check it out but he’s not available this month. It has to be an SSO 2 or higher, and I can’t go out there myself. So…how about it?”

Call me impetuous (not to mention a little bored) but I’m not stupid. And while I’m far enough down the management ladder that I have to squint to see daylight, I’m an SSO 3, which means I can sign off on petty cash authorizations up to the price of a pencil and get to sit in on interminable meetings, when I’m not tackling supernatural incursions or grappling with the eerie, eldritch horrors in Human Resources. I even get to represent my department on international liaison junkets, when I don’t dodge fast enough. “Not so quick—why can’t you go? Have you got a meeting scheduled, or something?” Most likely it’s a five course lunch with his opposite number from the Dustbin liaison committee, knowing Andy, but if so, and if I take the job, that’s all for the good: he’ll end up owing me.

Andy pulls a face. “It’s not the usual. I would go, but they might not let me out again.”

Huh? “‘They’? Who are ‘they’?”

“The Nurses.” He looks me up and down as if he’s never seen me before. Weird. What’s gotten into him? “They’re sensitive to the stench of magic. It’s okay for you, you’ve only been working here, what? Six years? All you need to do is turn your pockets inside out before you go, and make sure you’re not carrying any gizmos, electronic or otherwise. But I’ve been here coming up on fifteen years. And the longer you’ve been in the Laundry…it gets under your skin. Visiting the Funny Farm isn’t a job for an old hand, Bob. It has to be someone new and fresh, who isn’t likely to attract their professional attention.”

Call me slow, but finally I figure out what this is about. Andy wants me to go because he’s afraid.

(See, I told you the rules, didn’t I?)

* * *

Anyway, that’s why, less than a week later, I am admitted to a Lunatickal Asylum—for that is what the gothic engraving on the stone Victorian workhouse lintel assures me it is. Luckily mine is not an emergency admission: but you can never be too sure…

* * *

The old saw that there are some things that mortal men were not meant to know cuts deep in my line of work. Laundry staff—the Laundry is what we call the organization, not a description of what it does—are sometimes exposed to mind-blasting horrors in the course of our business. I’m not just talking about the usual PowerPoint presentations and self-assessment sessions to which any bureaucracy is prone: they’re more like the mythical Worse Things that happen at Sea (especially in the vicinity of drowned alien cities occupied by tentacled terrors). When one of our number needs psychiatric care, they’re not going to get it in a normal hospital, or via care in the community: we don’t want agents babbling classified secrets in public, even in the relatively safe confines of a padded cell. Perforce, we take care of our own.

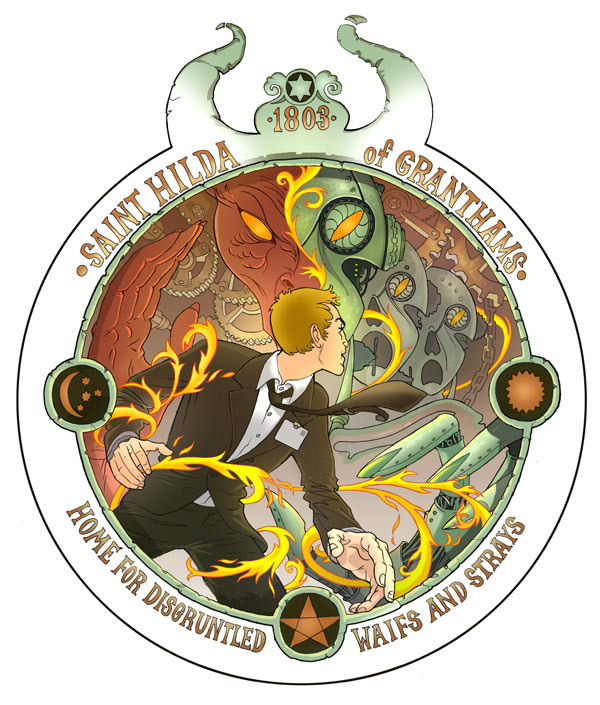

I’m not going to tell you what town the Funny Farm is embedded in. Like many of our establishments it’s a building of a certain age, confiscated by the government during the Second World War and not returned to its former owners. It’s hard to find; it sits in the middle of a triangle of grubby shopping streets that have seen better days, and every building that backs onto it sports a high, windowless, brick wall. All but one: if you enter a small grocery store, walk through the stock room into the back yard, then unlatch a nondescript wooden gate and walk down a gloomy, soot-stained alley, you’ll find a dank alleyway. You won’t do this without authorization—it’s protected by wards powerful enough to cause projectile vomiting in would-be burglars—but if you did, and if you followed the alley, you’d come to a heavy green wooden door surrounded by narrow windows with black-painted cast-iron bars. A dull, pitted plaque next to the doorbell proclaims it to be St Hilda of Grantham’s Home For Disgruntled Waifs And Strays. (Except that most of them aren’t so much disgruntled as demonically possessed when they arrive at these gates.)

It smells faintly of boiled cabbage and existential despair. I take a deep breath and yank the bell-pull.

Nothing happens, of course. I phoned ahead to make an appointment, but even so, someone’s got to unlock a bunch of doors and then lock them again before they can get to the entrance and let me in. “They take security seriously there,” Andy told me—“can’t risk some of the battier inmates getting loose, you know.”

“Just how dangerous are they?” I’d asked.

“Mostly they’re harmless—to other people.” He shuddered. “But the secure ward—don’t try and go there on your own. Not that the Sisters will let you, but I mean, don’t even think about trying it. Some of them are…well, we owe them a duty of care and a debt of honour, they fell in the line of duty and all that, but that’s scant consolation for you if a senior operations officer who’s succumbed to paranoid schizophrenia decides that you’re a BLUE HADES and gets hold of some red chalk and a hypodermic needle before your next visit, hmm?”

The thing is, magic is a branch of applied mathematics, and the inmates here are not only mad: they’re computer science graduates. That’s why they came to the attention of the Laundry in the first place, and it’s also why they ultimately ended up in the Farm, where we can keep them away from sharp pointy things and diagrams with the wrong sort of angles. But it’s difficult to make sure they’re safe. You can solve theorems with a blackboard if you have to, after all, or in your head, if you dare. Green crayon on the walls of a padded cell takes on a whole different level of menace in the Funny Farm: in fact, many of the inmates aren’t allowed writing implements, and blank paper is carefully controlled—never mind electronic devices of any kind.

I’m mulling over these grim thoughts when there’s a loud clunk from the door, and a panel just large enough to admit one person opens inward. “Mr Howard? I’m Dr. Renfield. You’re not carrying any electronic or electrical items or professional implements, fetishes, or charms?” I shake my head. “Good. If you’d like to come this way, please?”

Renfield is a mild-looking woman, slightly mousy in a tweed skirt and white lab coat, with the perpetually harried expression of someone who has a full Filofax and hasn’t worked out yet that her watch is losing an hour a day. I hurry along behind her, trying to guess her age. Thirty five? Forty five? I give up. “How many inmates do you have, exactly?” I ask.

We come to a portcullis-like door and she pauses, fumbling with an implausibly large key ring. “Eighteen, at last count,” she says. “Come on, we don’t want to annoy Matron. She doesn’t like people obstructing the corridors.” There are steel rails recessed into the floor, like a diminutive narrow-gauge railway. The corridor walls are painted institutional cream, and I notice after a moment that the light is coming through windows set high up in the walls: odd-looking devices like armoured-glass chandeliers hang from pipes, just out of reach. “Gas lamps,” Renfield says abruptly. I twitch. She’s noticed my surreptitious inspection. “We can’t use electric ones, except for Matron, of course. Come into my office, I’ll fill you in.”

We go through another door—oak, darkened with age, looking more like it belongs in a stately home than a Lunatick Asylum, except for the two prominent locks—and suddenly we’re in mahogany row: thick wool carpets, brass door-knobs, light switches, and over-stuffed armchairs. (Okay, so the carpet is faded with age and transected by more of the parallel rails. But it’s still Officer Country.) Renfield’s office opens off one side of this reception area, and at the other end I see closed doors and a staircase leading up to another floor. “This is the administrative wing,” she explains as she opens her door. “Tea or coffee?”

“Coffee, thanks,” I say, sinking into a leather-encrusted armchair that probably dates to the last but one century. Renfield nods and pulls a discreet cord by the door frame, then drags her office chair out from behind her desk. I can’t help noticing that not only does she not have a computer, but her desk is dominated by a huge and ancient manual typewriter—an Imperial Aristocrat ‘66’ with the wide carriage upgrade and adjustable tabulator, I guess, although I’m not really an expert on office appliances that are twice as old as I am—and one wall is covered in wooden filing cabinets. There might be as much as thirty megabytes of data stored in them. “You do everything on paper, I understand?”

“That’s right.” She nods, serious-faced. “Too many of our clients aren’t safe around modern electronics. We even have to be careful what games we let them play—Lego and Meccano are completely banned, obviously, and there was a nasty incident involving a game of Cluedo, back before my time: any board game that has a non-deterministic set of rules can be dangerous in the wrong set of hands.”

The door opens. “Tea for two,” says Renfield. I look round, expecting an orderly, and freeze. “Mr Howard, this is Nurse Gearbox,” she adds. “Nurse Gearbox, this is Mr Howard. He is not a new admission,” she says hastily, as the thing in the doorway swivels its head towards me with a menacing hiss of hydraulics.

Whirr-clunk. “Miss-TER How-ARD. Wel-COME to“—ching—“Sunt-HIL-dah’s“—hiss-clank. The thing in the very old-fashioned nurse’s uniform—old enough that its origins as a nineteenth-century nun’s habit are clear—regards me with unblinking panopticon lenses. Where its nose should be, something like a witch-finder’s wand points towards me, stellate and articulated: its face is a brass death mask, mouth a metal grille that seems to grimace at me in pointed distaste.

“Nurse Gearbox is one of our eight Sisters,” explains Dr Renfield. “They’re not fully autonomous“—I can see a rope-thick bundle of cables trailing from under the hem of the Sister’s floor-length skirt, which presumably conceals something other than legs—“but controlled by Matron, who lives in the two sub-basement levels under the administration block. Matron started life as an IBM 1602 mainframe, back in the day, with a summoning pentacle and a trapped class four lesser nameless manifestation constrained to provide the higher cognitive functions.”

I twitch. “It’s a grid, please, not a pentacle. Um. Matron is electrically powered?”

“Yes, Mr. Howard: we allow electrical equipment in Matron’s basement as well as here in the staff suite. Only the areas accessible to the patients have to be kept power-free. The Sisters are fully equipped to control unseemly outbursts, pacify the over-stimulated, and conduct basic patient care tasks. They also have Vohlman-Flesch Thaumaturgic Thixometers for detecting when patients are in danger of doing themselves a mischief, so I would caution you to keep any occult activities to a minimum in their presence—despite their hydraulic delay line controls, their reflexes are very fast.”

Gulp. I nod appreciatively. “When was the system built?”

The set of Dr. Renfield’s jaw tells me that she’s bored with the subject, or doesn’t want to go there for some reason. “That will be all, Sister.” The door closes, as if on oiled hinges. She waits for a moment, head cocked as if listening for something, then she relaxes. The change is remarkable: from stressed-out psychiatrist to tired housewife in zero seconds flat. She smiles tiredly. “Sorry about that. There are some things you really shouldn’t talk about in front of the Sisters: among other things, Matron is very touchy about how long she’s been here, and everything they hear, she hears.”

“Oh, right.” I feel like kicking myself.

“Did Mr. Newstrom brief you about this installation before he pitched you in at the deep end?”

Just when I thought I had a handle on her…“Not in depth.” (Let’s not mention the six sheet letter of complaint alleging staff brutality, scribbled in blue crayon on both sides of the toilet paper. Let’s not go into the fact that nobody has a clue how it was smuggled out, much less how it appeared on the table one morning in the executive boardroom, which is always locked overnight.) “I gather it’s pretty normal to fob inspections off on a junior manager.” (Let’s not mention just how junior.) “Is that a problem?”

“Humph.” Renfield sniffs. “You could say so. It’s a matter of necessity, really. Too much exposure to esoterica in the course of duty leaves the most experienced operatives carrying traces of, hmm, disruptive influences.” She considers her next words carefully. “You know what our purpose is, don’t you? Our job is to isolate and care for members of staff who are a danger to themselves and others. That’s why such a small facility—we only have thirty beds—has two doctors on staff: it takes two to sign the committal papers. Matron and the Sisters are immune to cross-infection and possession, but have no legal standing, so Dr. Hexenhammer and I are needed.”

“Right.” I nod, trying to conceal my unease. “So the Sisters have a tendency to react badly to senior field agents?”

“Occasionally.” Her cheek twitches. “Although they haven’t made a mistake and tried to forcibly detain anyone who wasn’t at risk for nearly thirty years now.” The door opens again, without warning. This time, Sister is pushing a trolley, complete with teapot, jug, and two cups and saucers. The trolley wheels fit perfectly on the narrow-gauge track, and the way Nurse Gearbox shunts it along makes me think wheels. “Thank you, Sister, that will be all,” Renfield says, taking the trolley.

“So what clients do you have at present?” I ask.

“We have eighteen,” she says, without missing a beat. “Milk or sugar?”

“Milk, no sugar. Nobody at head office seems able to tell me much about them.”

“I don’t see why not—we file regular updates with Human Resources,” she says, pouring the tea.

I consider my next words carefully: no need to mention the confusing incident with the shredder, the medical files, and the photocopies of Peter-Fred’s buttocks at last year’s Christmas party. (Never mind the complaint, which isn’t worth the toilet paper it was scribbled on except insofar as it proves that the Funny Farm’s cordon sanitaire is leaking. One of the great things about ISO9000 compliant organizations is that not only is there a form for everything, but anything that isn’t submitted on the correct form can be ignored.) “It’s the paper thing, apparently. Manual typewriters don’t work well with the office document management system, and someone tried to feed them to a scanner a couple of years ago. Then they sent the originals for recycling without proof-reading the scanner output. Anyway, it turns out that we don’t have a completely accurate idea of who’s on long-term remand here, and HR want their superannuation files bringing up to date, as a matter of some urgency.”

Renfield sighs. “So someone had an accident with a shredder again. And no photocopies?” She looks at me sharply for a moment: “Well, I suppose that’s just typical. We’re just another of those low-priority outposts nobody gives a damn about. I suppose I should be grateful they sent someone to look into it…” She takes a sip of tea. “We’ve got fourteen short-stay patients right now, Mr Howard. Of those, I think the prognosis is good in all cases, except perhaps Merriweather…if you give me your desk number I’ll post you a full list of names and payroll references tomorrow. The four long term patients are another matter. They live in the secure wing, by the way. All of them have a nurse of their own, just in case. Three of them have been here so long that they don’t have current payroll numbers—the system was first computerized in 1972, and they’d all been permanently decertified for duty before that point—and one of them, between you and me, I’m not even sure what his name is.”

I nod, trying to look encouraging. The complaint I’m supposed to investigate apparently came from one of the long-term patients. The question is, which one? Nobody’s sure: the doorman on the night shift when the document showed up isn’t terribly communicative (he’s been dead for some years himself), and the CCTV system didn’t spot anything. Which is in itself suggestive—the Laundry’s HQ CCTV surveillance is rather special, extremely hard to deceive, and guaranteed not to be hooked up to the SCORPION STARE network any more, which would be the most obvious route to suborning it. “Perhaps you could introduce me to the inmates? The transients first, then the long-term ones?”

She looks a little shocked. “But they’re the long term residents! I assure you, they each need a full-time Sister’s attention just to keep them under control!”

“Of course,” I shrug, trying to look embarrassed (it’s not hard): “but HR have got a bee in their bonnet about some European Directive on workplace health and safety and long-term disability resource provisioning that requires them to appoint a patient advocate to mediate with the ombudsman in disputes over health and safety conditions”—I shrug again. “It’s bullshit. You know it and I know it. But we’ve got to comply, or Questions will be Asked. This is the civil service, after all. And they’re still technically Laundry employees, even if they’ve been remanded into long-term care, so someone has to do the job. My managers played spin-the-bottle and I got the job, so I’ve got to ask you. If you don’t mind?”

“If you insist, I’m sure something can be arranged,” Renfield concedes. “But Matron won’t be happy about you visiting the secure wing. It’s very irregular—she likes to keep a firm grip on it. It’ll take a while to sort a visit out, and if any of them get wind…”

“Well, then, we’d just better make it a surprise, and the sooner we get it over with, the sooner I’ll be out of your hair!” I grin like a loon. “They told me about the observation gallery. Would you mind showing me around?”

* * *

We do the short-stay ward first. The ward is arranged around a corridor, with bathrooms and a nursing station at either end, and individual rooms for the patients. There’s a smoking room off to one side, with a yellow patina to the white gloss paint around the door frame. The smoking room is empty but for a huddle of sad-looking leather armchairs and an imposing wall-board covered in health and safety notices (including the obligatory “Smoking is Illegal” warning). If it wasn’t for the locks and the observation windows in the doors, it could be mistaken for the day room of a genteel, slightly decaying Victorian railway hotel, fallen on hard times.

The patients are another matter.

“This is Henry Merriweather,” says Dr Renfield, opening the door to Bed Three. “Henry? Hello? I want you to meet Mr Howard. He’s here to conduct a routine inspection. Hello? Henry?”

Bed Three is actually a cramped studio flat, featuring a small living room with sofa and table, and separate bedroom and toilet areas opening off it opposite the door. A wind-up gramophone with a flaring bell-shaped horn sits atop a hulking wooden sideboard, stained almost black. There’s a newspaper, neatly folded, and a bowl of fruit. The frosted window glass is threaded with wire, but otherwise there’s little to dispel the illusion of hospitality, except for the occupant.

Henry squats, cross-legged, on top of the polished wooden table. His head is tilted in my direction, but he’s not focusing on me. He’s dressed in a set of pastel-striped pyjamas the like of which I haven’t seen this century. His attention is focused on the Sister waiting in the corridor behind us. His face is a rictus of abject terror, as if the automaton in the starched pinafore is waiting to pull his fingers to pieces, joint by joint, as soon as we leave.

“Hello?” I say tentatively, and wave a hand in front of him.

Henry jack-knifes to his feet and tumbles off the table backwards, making a weird gobbling noise that I mistake at first for laughter. He backs into the corner of the room, crouching, and points past me: “auditor! Auditor!”

“Henry?” Renfield steps sideways around me. She sounds concerned. “Is this a bad time? Is there anything I can do to help?”

“You—you—” His wobbly index finger points past me, twitching randomly. “Inspection! Inspection!”

Renfield obviously used the wrong word and set him off. The poor bastard’s terrified, half out of his tree with fear. My stomach just about climbs out through my ribs in sympathy: the auditors are one of my personal nightmares, and Henry (that’s Senior Scientific Officer Third, Henry Merriweather, Operations Research and Development Group) may be half-catatonic and a danger to himself, but he’s got every right to be afraid of them. “It’s all right, I’m not”—There’s a squeaking grinding noise behind me.

Whirr-Clunk. “Miss-TER MerriWEATHER. GO to your ROOM.” Click. “Time for BED. IMM-ediateLY.” Click-clunk. Behind me, Nurse Flywheel is blocking the door like a starched and pintucked Dalek: she brandishes a cast-iron sink plunger menacingly. “IMM-ediateLY!”

“Override!” barks Renfield. “Sister! Back away!” To me, quietly: “the Sisters respond badly when inmates get upset. Follow my lead.” To the Sister, who is casting about with her stalk-like Thaumic Thixometer: “I have control!”

Merriweather stands in the corner, shaking uncontrollably and panting as the robotic nurse points at him for a minute. We’re at an impasse, it seems. Then: “DocTOR—Matron says the patIENT must go to bed. You have CON-trol.” Clunk-whirr. The sister withdraws, rotates on her base, and glides backward along her rails to the nursing station.

Renfield nudges the door shut with one foot. “Mr Howard, would you mind standing with your back to the door? And your head in front of that, ah, spy-hole?”

“You’re not, not, nuh-huh—” Merriweather gobbles for words as he stares at me.

I spread my hands. “Not an auditor,” I say, smiling.

“Not an—an—” His mouth falls open and his eyes shut. A moment later, I see the moisture trails on his cheeks as he begins to weep with quiet desperation.

“He’s having a bad day,” Renfield mutters in my direction. “Here, let’s get you to bed, Henry.” She approaches him slowly, but he makes no move to resist as she steers him into the small bedroom and pulls the covers back.

I stand with my back to the door the whole time, covering the observation window. For some reason, the back of my neck is itching. I can’t help thinking that Nurse Flywheel isn’t exactly the chatty talkative type who’s likely to put her feet up and relax with a nice cup of tea. I’ve got a feeling that somewhere in this building, an unblinking red-rimmed eye is watching me, and sooner or later I’m going to have to meet its owner.

* * *

Andy was afraid.

Well, I’m not stupid; I can take a hint. So right after he asked me to go down to St Hilda’s and find out what the hell was going on, I plucked up my courage and went and knocked on Angleton’s office door.

Angleton is not to be trifled with. I don’t know anyone else currently alive and in the organization who could get away with misappropriating the name of the CIA’s legendary chief of counter-espionage as a nom de guerre. I don’t know anyone else in the organization whose face is visible in circa-1942 photographs of the Laundry’s line-up, either, barely changed across all those years. Angleton scares the bejeezus out of most people, myself included. Study the abyss for long enough and the abyss will study you right back; Angleton’s qualified to chair a university department of necromancy—if any such existed—and meetings with him can be quite harrowing. Luckily the old ghoul seems to like me, or at least not to view me with the distaste and disdain he reserves for Human Resources or our political masters. In the wizened, desiccated corners of what passes for his pedagogical soul he evidently longs for a student, and I’m the nearest thing he’s got right now.

Knock, knock.

“Enter.”

“Boss? Got a minute?”

“Sit, boy.” I sat. Angleton bashed away at the keyboard of his device for a few more seconds, then pulled the carbon papers out from under the platen—for really secret secrets in this line of work, computers are flat-out verboten—and laid them face-down on his desk, then carefully draped a stained tea-towel over them. “What is it?”

“Andy wants me to go and conduct an unscheduled inspection of the Funny Farm.”

Whoa. Angleton stares at me, fully engaged. “Did he say why?” he asks, finally.

“Well.” How to put it? “He seems to be afraid of something. And there’s some kind of complaint. From one of the inmates.”

Angleton props his elbows on the desk and makes a steeple of his bony fingers. A minute passes before a cold wind blows across the charnel house roof: “well.”

I have never seen Angleton nonplussed before. The effect is disturbing, like glancing down and realizing that, like Wile E. Coyote, you’ve just run over the edge of a cliff and are standing on thin air. “Boss?”

“What exactly did Andy say?” Angleton asks slowly.

“We received a complaint.” I briefly outline what I know about the shit-stirring missive. “Something about one of the long-stay inmates. And I was just wondering, do you know anything about them?”

Angleton peers at me over the rims of his bifocals. “As a matter of fact I do,” he says slowly. “I had the privilege of working with them. Hmm. Let me see.” He unfolds creakily to his feet, turns, and strides over to the shelves of ancient Eastlight files that cover the back wall of his office. “Where did I put it…”

Angleton going to the paper files is another whoa! moment. He keeps most of his stuff in his Memex, the vast, hulking microfilm mechanism built into his desk. If it’s still printed on paper then it’s really important. “Boss?”

“Yes?” he says, without turning away from his search.

“We don’t know how the message got out,” I say. “Isn’t it supposed to be a secure institution?”

“Yes, it is. Ah, that’s more like it.” Angleton pulls a box file from its niche and blows vigorously across its upper edge. Then he casually opens it. There’s a pop and a sizzle of ozone as the ward lets go, harmlessly bypassing him—he is, after all, its legitimate owner. “Hmm, in here somewhere…”

“Isn’t it supposed to be leak-proof, by definition?”

“I’m getting to that. Be patient, Bob.” There’s a waspish note in his voice and I shut up hastily.

A minute later, Angleton pulls a mimeographed booklet from the file and closes the lid. He returns to the desk, and slides the booklet towards me.

“I think you’d better read this first, then go and do what Andy wants,” he says slowly. “Be a good boy and copy me on your detailed itinerary before you depart.”

I read the cover of the booklet, which is dog-eared and dusty. There’s a picture of a swell guy in a suit and a gal in a fifties beehive hairdo sitting in front of a piece of industrial archaeology. The title reads: POWER, COOLING, AND SUBSTATION REQUIREMENTS FOR YOUR IBM S/1602-M200. I sneeze, puzzled. “Boss?”

“I suggest you read and memorize this booklet, Bob. It is not impossible that there will be an exam and you really wouldn’t want to fail it.”

My skin crawls. “Boss?”

Pause.

“It’s not true that the Funny Farm is entirely leak-proof, Bob. It’s surrounded by an air-gap but it was designed to leak under certain very specific conditions. I find it troubling that these conditions do not appear to apply in the present circumstances. In addition to memorizing this document you might want to review the files on GIBBOUS MOON and AXIOM REFUGE before you go.” Pause. “And if you see Cantor, give my regards to the old coffin-dodger. I’m particularly interested in hearing what he’s been up to for the past thirty years…”

* * *

Renfield takes me back to the smoking room and shuts the door. “He’s having a bad day, I’m afraid.” She pulls out a cardboard packet and extracts a cigarette. “Smoke?”

“Uh, no thanks.” The sash windows are nailed shut and their frames painted over. There’s a louvered vent near the top of the windows, grossly unfit for purpose: I try not to breathe too deeply. “What happened to him?”

She strikes a match and contemplates the flame for a moment. “Let’s see. He’s forty two. Married, two kids—he talks about them. Wife’s a schoolteacher, his deep cover is that he works in MI6 clerical.” (You’re not supposed to talk about your work to your partner, but it’s difficult enough that we’ve been given dispensation to tell little white lies—and if necessary, HR will back them up.) “He’s not field-qualified—mostly he does theory—but he worked for Q Division and he was on secondment to the Abstract Attractor Working Group when he fell ill.”

In other words, he’s a theoretical thaumaturgist. Magic being a branch of applied mathematics, when you carry out certain computational operations, it has echoes in the Platonic realm of pure mathematics—echoes audible to beings whose true nature I cannot speak of, on account of doing so being a violation of the Official Secrets Act. Theoretical Thaumaturgists are the guys who develop new efferent algorithms (or, colloquially, “spells”): it’s an occupation with a high attrition rate.

“He’s convinced the Auditors are after him for thinking inappropriate thoughts on organization time. There’s an elaborate confabulation, and it looks a little like paranoid schizophrenia at first glance, but underneath…we sent him to our Trust hospital for an MRI scan and he’s got the characteristic lesions.”

“Lesions?”

She takes a deep drag from the cigarette. “His prefrontal lobes look like Swiss cheese. It’s one of the early signs of Krantzberg Syndrome. If we can keep him isolated from work for a couple more months, then retire him to a nice quiet desk job, we might be able to stabilize him. K Syndrome’s not like Alzheimer’s: if you remove the insult it frequently goes into remission. Mind you, he may also need a course of chemotherapy. At various times my predecessors tried electroconvulsive treatment, prefrontal lobotomy, neuroleptics, daytime television, LSD—none of them work consistently or reliably. The best treatment still seems to be bed rest followed by work therapy in a quiet, undemanding office environment.” Blue cloud spirals toward the ceiling. “But he’ll never run a great summoning again.”

I’m beginning to regret not accepting her offer of a cigarette, and I don’t even smoke. My mouth’s dry. I sit down: “Do we have any idea what causes K Syndrome?” I’ve skimmed GIBBOUS MOON, but the medical jargon didn’t mean much to me; and AXIOM REFUGE was even less helpful. (It turned out to be a dense mathematical treatise introducing a notation for describing certain categories of topological defect in a twelve-dimensional space.) Only the power supply for the mainframe—presumably the one Matron used—seemed remotely relevant to the job in hand.

“There are several theories.” Renfield twitches ash on the threadbare carpet as she paces the room. “It tends to hit theoretical computational demonologists after about twenty years: Merriweather is unusually young. It also hits people who’ve worked in high-thaum fields for too long. Initial symptoms include mild ataxia—you saw his hand shaking?—and heightened affect: it can be mistaken for bipolar disorder or hyperactivity. There’s also the disordered thinking and auditory hallucinations typical of some types of schizophrenia.” She pauses to inhale. “There are two schools of thought, if you leave out the Malleus Maleficarum stuff about souls contaminated by demonic effusions: one is that exposure to high thaum fields cause progressive brain lesions. Trouble is, it’s rare enough that we haven’t been able to quantify that, and—”

“The other theory?” I prod.

“My favourite.” She nearly smiles. “Computational demonology—you carry out calculations, you prove theorems; somewhere else in the platonic realm of mathematics Listeners notice your activities and respond, yes? Well, there’s some disagreement over this, but the current orthodoxy in neurophysiology is that the human brain is a computational organ. We can carry out computational tasks, yes? We’re not very good at it, and at an individual neurological level there’s no mechanism that might invoke the core Turing theorems, but…if you think too hard about certain problems you might run the risk of carrying out a minor summoning in your own head. Nothing big enough or bad enough to get out, but…those florid daydreams? And the sick feeling afterwards because you can’t quite remember what it was about? Something in another universe just sucked a microscopic lump of neural tissue right out of your intraparietal sulcus, and it won’t grow back.”

Urk. Not so much “use it or lose it” as “use it and lose it”, then. Could be worse, could be a NAND gate in there…“Do we know why some people suffer from it and others don’t?”

“No idea.” She drops what’s left of her cigarette and grinds it under the heel of a sensible shoe. She catches my eye: “Don’t worry about it, the Sisters keep everything orderly,” she says. “Do you know what you want to do next?”

“Yes,” I say, damning myself for a fool before I take the next logical step: “I want to talk to the long term inmates.”

* * *

I’m half hoping Renfield will put her foot down and refuse point blank to let me do it, but she only puts up a token fight: she makes me sign a personal injury claims waiver and scribble out a written order instructing her to show me the gallery. So why do I feel as if I’ve somehow been outmanoeuvred?

After I finish signing forms to her heart’s content, she uncaps an ancient and battered speaking tube beside her desk and calls down it. “Matron, I am taking the inspector to see the observation gallery, in accordance with orders from Head Office. He will then meet with the inmates in Ward Two. We may be some time.” She screws the cap back on before turning to me apologetically: “It’s vital to keep Matron informed of our movements, otherwise she might mistake them for an escape attempt and take appropriate action.”

I swallow. “Does that happen often?” I ask, as she opens the office door and stalks towards the corridor at the other end.

“Once in a while a temporary patient gets stir-crazy.” She starts up the stairs. “But the long-term residents…no, not so much.”

Upstairs, there’s a landing very similar to the one we just left—with one big exception: a narrow, white-painted metal door in one wall, stark and raw, secured by a shiny brass padlock and a set of wards so ugly and powerful that they make my skin crawl. There are no narrow-gauge rails leading under this door, no obvious conductive surfaces, nothing to act as a conduit for occult forces. Renfield fumbles with a huge key ring at her side, then unfastens the padlock. “This is the way in via the observation gallery,” she says. “There are a couple of things to bear in mind. Firstly, the Nurses can’t guarantee your safety: if you get in trouble with the prisoners, you’re on your own. Secondly, the gallery is a Faraday cage, and it’s thaumaturgically grounded too—it’d take a black mass and a multiple sacrifice to get anything going in here. You can observe the apartments via the periscopes and hearing tubes provided. That’s our preferred way—you can go into the ward by proceeding to the other end of the gallery, but I’d be very grateful if you could refrain from doing so unless it’s absolutely essential. They’re difficult enough to manage as it is. Finally, if you insist on meeting them, just try to remember that appearances can be deceptive.”

“They’re not demented,” she adds: “just extremely dangerous. And not in a Hannibal Lecter bite-your-throat-out sense. They—the long-term residents—aren’t regular Krantzberg Syndrome cases. They’re stable and communicative, but…you’ll see for yourself.”

I change the subject before she can scare me any more. “How do I get into the ward proper? And how do I leave?”

“You go down the stairs at the far end of the gallery. There’s a short corridor with a door at each end. The doors are interlocked so that only one can be open at a time. The outer door will lock automatically behind you when it closes, and it can only be unlocked from a control panel at this end of the viewing gallery. Someone up here”—meaning, Renfield herself—“has to let you out.” We reach the first periscope station in the viewing gallery. “This is room two. It’s currently occupied by Alan Turing.” She notices my start: “Don’t worry, it’s just his safety name.”

(True names have power, so the Laundry is big on call by reference, not call by value; I’m no more “Bob Howard” than the “Alan Turing” in room two is the father of computer science and applied computational demonology.)

She continues: “The real Alan Turing would be nearly a hundred by now. All our long-term residents, are named for famous mathematicians. We’ve got Alan Turing, Kurt Godel, Georg Cantor, and Benoit Mandelbrot. Turing’s the oldest, Benny is the most recent—he actually has a payroll number, 16.”

I’m in five digits—I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. “Who’s the nameless one?” I ask.

“That would be Georg Cantor,” she says slowly. “He’s probably in room four.”

I bend over the indicated periscope, remove the brass cap, and peer into the alien world of the nameless K Syndrome survivor.

I see a whitewashed room, quite spacious, with a toilet area off to one side and a bedroom accessible through a doorless opening—much like the short term ward. The same recessed metal tracks run around the floor, so that a Nurse can reach every spot in the apartment. There’s the usual comfortable, slightly shabby furniture, a pile of newspapers at one side of the sofa and a sideboard with a wind-up gramophone. In the middle of the floor there’s a table, and two chairs. Two men sit on either side of an ancient travel chess set, leaning over a game that’s clearly in its later stages. They’re both old, although how old isn’t immediately obvious—one has gone bald, and his liver-spotted pate reminds me of an ancient tortoise, but the other still has a full head of white hair and an impressive (but neatly trimmed) beard. They’re wearing polo shirts and grey suits of a kind that went out of fashion with the fall of the Soviet Union. I’m willing to bet there are no laces in their brogues.

The guy with the hair makes a move, and I squint through the periscope. That was wrong, wasn’t it? I realize, trying to work out what’s happening. Knights don’t move like that. Then the implication of something Angleton said back in the office sinks in, and an icy sweat prickles in the small of my back. “Do you play chess?” I ask Dr Renfield without looking round.

“No.” She sounds disinterested. “It’s one of the safe games—no dice, no need for a pencil and paper. And it seems to be helpful. Why?”

“Nothing, I hope.” But my hopes are dashed a moment later when turtle-head responds with a sideways flick of a pawn, two squares to the left, and takes beardy’s knight. Turtle-head drops the knight into a biscuit-tin along with the other disused pieces; it sticks to the side, as if magnetized. Beardy nods, as if pleased, then leans back and glances up.

I recoil from the periscope a moment before I meet his eyes. “The two players. Guy like a tortoise, and another with a white beard and a full head of hair. They are…?”

“That’d be Turing and Cantor. Turing used to be a Detached Special Secretary in Ops, I think; we’re not sure who or what Cantor was, but he was someone senior.” I try not to twitch. DSS is one of those grades, the fuzzy ones that HR aren’t allowed to get their grubby little fingers on. I think Angleton’s one. (Scuttlebutt is that it’s an acronym for Deeply Scary Sorcerer.) “They play chess every afternoon for a couple of hours—for as long as I can remember.”

Right. I peer down the periscope again, looking at the game of not-chess. “Tell me about Dr Hexenhammer. Where is he?”

“Julius? I think he’s in an off-site meeting or something today,” she says vaguely. “Why?”

“Just wondering. How long has he been working here?”

“Before my time.” She pauses. “About thirty years, I think.”

Oh dear. “He doesn’t play chess either,” I speculate, as Cantor’s king makes a knight’s move and Turing’s queen’s pawn beats a hasty retreat. A nasty suspicious thought strikes me—about Renfield, not the inmates. “Tell me, do Cantor and Turing play chess regularly?” I straighten up.

“Every afternoon for a couple of hours. Julius says they’ve been doing it for as long as he can remember. It seems to be good for them.” I look at her sharply. Her expression is vacant: wide awake but nobody home. The hairs on the back of my neck begin to prickle.

Right. I am getting a very bad feeling about this. “I need to go and talk to the patients now. In person.” I stand up and hook the cap back over the periscope. “Stick around for fifteen minutes, please, in case I need to leave in a hurry. Otherwise,” I glance at my watch, “it’s twenty past one. Check back for me every hour on the half hour.”

“Are you certain you need to do this?” Her eyes narrow, suddenly alert once more.

“You visit with the patients, don’t you?” I raise an eyebrow. “And you do it on your own, with Dr Hexenhammer up here to let you out if there’s a problem. And the Sisters.”

“Yes but—” She bites her tongue.

“Yes?” I give her the long stare.

“I’m rubbish with computers!” she bursts out. “But you’re at risk!”

“Well, there aren’t any computers except Matron down there, are there?” I grin crookedly, trying not to show my unease. (Best not to dwell upon the fact that before 1945 “computer” was a job description, not a machine.) “Relax, it’s not contagious.”

She shrugs in surrender, then gestures at the far end of the observation gallery, where a curious contraption sits above a pipe: “That’s the alarm. If you want a Sister, pull the chain with the blue handle. If you want a general alarm which will call the duty psychiatrist, pull the red handle. There are alarm handles in every room.”

“Okay.” Blue for a Sister, Red for a psychiatrist who is showing all the signs of being under a geas or some other form of compulsion—except that I can’t check her out without attracting Matron’s unwanted attention and probably tipping my hand. I begin to see why Andy didn’t want to open this particular can of worms. “I can deal with that.”

I head for the stairs at the far end of the gallery.

* * *

There’s nothing homely about the short corridor that leads from the bottom of the staircase to the Secure Wing. Whitewashed brick walls, glass bricks near the ceiling to admit a wan echo of daylight, and doors made of metal that have no handles. Normally going into a situation like this I’d be armed to the teeth, invocations and efferent subroutines loaded on my PDA, hand of glory in my pocket and a necklace of garlic bulbs around my neck: but this time I’m naked, and nervous as a frog in his birthday suit. The first door gapes open, waiting for me. I walk past it, and try not to jump out of my skin when it rattles shut behind me with a crash. There’s a heavy clunk from the door ahead. As I reach it and push, it swings open to reveal a corridor floored in parquet. An old codger in a green tweed suit and bedroom slippers is shuffling out of an opening at one side, clutching an enameled metal mug full of tea. He looks at me. “Why, hello!” he croaks. “You’re new here, aren’t you?”

“You could say that.” I try to smile. “I’m Bob. Who are you?”

“Depends who’s asking, young feller. Are you a psychiatrist?”

“I don’t think so.”

He shuffles forward, heading towards a side bay that, as I approach it, turns out to be a day room of some sort. “Then I’m not Napoleon Bonaparte!”

Oh, very droll. The terror is fading, replaced by a sense of disappointment. I trail after him: “The staff have names for you all. Turing, Cantor, Mandelbrot, and Godel. You’re not Cantor or Turing. That makes you one of Mandelbrot or Godel.”

“So you’re undecided?” There’s a coffee table with a pile of newspapers on it in the middle of the day room, a couple of elderly chesterfields and three armchairs that could have been looted from an old age home some time before the First World War. “And in any case, we haven’t been formerly introduced. So you might as well call me Alice.”

Alice—or Mandelbrot or Godel or whoever he is—sits down. The armchair nearly swallows him. He beams at my bafflement, delighted to have found a new victim for his doubtless-ancient puns.

“Well, Alice. Isn’t this quite some rabbit hole you’ve fallen down?”

“Yes, but it’s just the right size!” He seems to appreciate having somebody to talk to. “Do you know why you’re here?”

“Yup.” I see an expression of furtive surprise steal across his face. I nod, affably. Try to mess with my head, sonny? I’ll mess with yours. Except that this guy is quite possibly a DSS, and if it wasn’t for the constant vigilance of the Sisters and the distinct lack of electricity hereabouts, he could turn me inside out as soon as look at me. “Do you know why you’re here?”

“Absolutely!” He nods back at me.

“So now that we’ve established the preliminaries, why don’t we cut the bullshit?”

“Well.” He takes a cautious sip of his tea and the wrinkles on his forehead deepen. “I suppose the Board of Directors want a progress report.”

If the sofa I was perched on wasn’t a relative of a venus flytrap my first reaction would leave me clinging to the ceiling. “The who want a—”

“Not the band, the Board.” He looks mildly irritated. “It’s been years since they last sent someone to spy on us.”

Okay, so this is the Funny Farm; I should have been expecting delusions. Play nice, Bob. “What are you supposed to be doing here?” I ask.

“Oh Lord.” He rolls his eyes. “They sent a tabula rasa again?” He raises his voice: “Kurt, they sent us a tabula rasa again!”

More shuffling. A stooped figure, shock-headed with white hair, appears in the doorway. He’s wearing tinted round spectacles that look like they fell off the back of a used century. “What? What?” He demands querulously.

“He doesn’t know anything,” Alice confides in—this must be Godel, I realise, which means Alice is Mandelbrot—Godel, then with a wink at me: “he doesn’t know anything, either.”

Godel shuffles into the rest room. “Is it tea-time already?”

“No!” Mandelbrot puts his mug down. “Get a watch!”

“I was only asking because Alan and Georg are still playing—”

This has gone far enough. Apprehension dissolves into indignation: “It’s not chess!” I point out. “And none of you are insane.”

“Sssh!” Godel looks alarmed. “The Sisters might overhear!”

“We’re alone, except from Dr Renfield upstairs, and I don’t think she’s paying as much attention to what’s going on down here as she ought to.” I stare at Godel. “In fact, she’s not really one of us at all, is she? She’s a shrink who specializes in K Syndrome, and none of you are suffering from K Syndrome. So what are you doing in here?”

“Fish-slice! Hatstand!” Godel pulls an alarming face, does a two-step backwards, and lurches into the wall. Having shared a house with Pinky and Brains, I am not impressed: as displays of ‘look at me, woo-woo’ go, Godel’s is pathetic. Obviously he’s never met a real schizophrenic.

“One of you wrote a letter, alleging mistreatment by the staff. It landed on my boss’s desk and he sent me to find out why.”

THUD. Godel bounces off the wall again, showing remarkable resilience for such old bones. “Do shut up old fellow,” chides Mandelbrot; “you’ll attract Her attention.”

“I’ve met someone with K Syndrome, and I shared a house with some real lunatics once,” I hint. “Save it for someone who cares.”

“Oh bother,” says Godel, and falls silent.

“We’re not mad,” Mandelbrot admits. “We’re just differently sane.”

“Then why are you here?”

“Public health.” He takes a sip of tea and pulls a face. “Everyone else’s health. Tell me, do they still keep an IBM 1602 in the back of the steam ironing room?” I must look blank because he sighs deeply and subsides into his chair. “Oh dear. Times change, I suppose. Look, Bob, or whoever you call yourself—we belong here. Maybe we didn’t when we first checked in for the weekend seminar, but we’ve lived here so long that…you’ve heard of care in the community? This is our community. And we will be very annoyed with you if you try to make us leave.”

Whoops. The idea of a very annoyed DSS, with or without a barbaric, pun-infested sense of humour, is enough to make anyone’s blood run cold. “What makes you think I’m going to try and make you leave?”

“It’s in the papers!” Godel squawks like an offended parrot. “See here!” He brandishes a tabloid at me and I take it, disentangling it from his fingers with some difficulty. It’s a local copy of the Metro, somewhat sticky with marmalade, and the headline of the cover blares: “NHS TRUST TO SELL ESTATE IN PFI DEAL“.

“Um. I’m not sure I follow.” I look to Mandelbrot in hope.

“We haven’t finished yet! But they’re selling off all the hospital Trust’s property!” Mandelbrot bounces in his chair. “What about St Hilda’s? It was requisitioned from the St James charitable foundation back in 1943, and for the past ten years the Ministry of Defence been giving all those old wartime properties back to their owners to sell off to the developers. What about us?”

“Whoa!” I drop the newspaper and hold my hands up. “Nobody tells me these things!”

“Told you!” crows Godel. “He’s part of the conspiracy!”

“Hang on”—I think fast—“this isn’t a normal MoD property, is it? It’ll have been shuffled under the rug back in 1946 as part of the post-war settlement. We’d really have to ask the Audit Department about who owns it, but I’m pretty sure it’s not owned by any NHS Trust, and they won’t simply give it back“—my brain finally catches up with my mouth—“what weekend seminar?”

“Oh bugger,” says a new voice from the doorway, a rich baritone with a hint of a scouse accent: “he’s not from the Board.”

“What did I tell you?” Godel screeches. “It’s a conspiracy! He’s from Human Resources! They sent him to evaluate us!”

I am quickly getting a headache. “Let me get this straight. Mandelbrot, you checked in thirty years ago for a weekend seminar, and they put you in the secure ward? Godel: I’m not from HR, I’m from Ops. You must be Cantor, right? Angleton sends his regards.”

That gets his attention. “Angleton? The skinny young whipper-snapper’s still warming a chair, is he?” Godel looks delighted. “Excellent!”

“He’s my boss. And I want to know the rules of that game you were just playing with Turing.”

Three pairs of eyes swivel to point at me—four, for they are joined by the last inmate, standing in the doorway—and suddenly I feel very small and very vulnerable.

“He’s sharp,” says Mandelbrot. “Too bad.”

“How do we know he’s telling the truth?” Godel’s screech is uncharacteristically muted. “He could be from the Opposition! KGB, Department 16! Or GRU, maybe.”

“The Soviet Union collapsed a few decades ago,” volunteers Turing. “It said so in the Telegraph.”

“Black Chamber, then.” Godel sounds unconvinced.

“What do you think the rules are?” asks Cantor, a drily amused expression stretching the wrinkles around his eyes.

“You’ve got pencils.” I can see one from here, sitting on the sideboard on top of a newspaper folded at the crossword page. “And, uh…” what must the world look like from an inmate’s point of view? “Oh. I get it.”

(The realisation is blinding, sudden, and makes me feel like a complete idiot.)

“The hospital! There’s no electricity, no electronics—no way to get a signal out—but it works both ways! You’re inside the biggest damn grounded defensive pentacle this side of HQ, and anything on the outside trying to get in has got to get past the defences”—because that’s what the Sisters are really about: not nurses but perimeter guards—“you’re a theoretical research cell, aren’t you?”

“We prefer to call ourselves a think tank.” Cantor nods gravely.

“Or even”—Mandelbrot takes a deep breath—“a brains trust!”

“A-ha! AhaHAHAHA! Hic.” Godel covers his mouth, face reddening.

“What do you think the rules are?” Cantor repeats, and they’re still staring at me, as if, as if…

“Why does it matter?” I ask. I’m thinking that it could be anything; a 2,5 universal Turing machine encoded in the moves of the pawns—that would fit—whatever it is, it’s symbolic communication, very abstract, very pared-back, and if they’re doing it in this ultimately firewalled environment and expecting to report directly to the Board it’s got to be way above my security clearance—

“Because you’re acting cagey, lad. Which makes you too bright for your own good. Listen to me: just try to convince yourself that we’re playing chess, and Matron will let you out of here.”

“What’s thinking got to do with”—I stop. It’s useless pretending. “Fuck. Okay, you’re a research cell working on some ultimate black problem, and you’re using the Farm because it’s about the most secure environment anyone can imagine, and you’re emulating some kind of minimal universal Turing machine using the chess board. Say, a 2,5 UTM—two registers, five operations—you can encode the registers positionally in the chess board’s two dimensions, and use the moves to simulate any other universal Turing machine, or a transform in an eleven-dimensional manifold like AXIOM REFUGE—”

Godel’s waving frantically: “She’s coming! She’s coming!” I hear doors clanging in the distance.

Shit. “But why are you so afraid of the Nurses?”

“Back channels,” Cantor says cryptically. “Alan, be a good lad and try to jam the door for a minute, will you? Bob, you are not cleared for what we’re doing here, but you can tell Angleton that our full report to the board should be ready in another eighteen months.” Wow—and they’ve been here since before the Laundry computerised its payroll system in the 1970s? “Are you absolutely sure they’re not going to sell St Hilda’s off to build flats for yuppies? Because if so, you could do worse than tell Georg here, it’ll calm him down—”

“Get me out of here and I’ll make damned sure they don’t sell anything off!” I say fervently. “Or rather, I’ll tell Angleton. He’ll sort things out.” When I remind what’s going on here, they’ll be no more inclined to sell off St Hilda’s than they would be to privatize an atomic bomb.

Something outside is rumbling and squealing on the metal rails. “You’re sure none of you submitted a complaint about staff brutality?”

“Absolutely!” Godel bounces up and down excitedly.

“It must have been someone else.” Cantor glances at the doorway: “You’d better run along. It sounds as if Matron is having second thoughts about you.”

I’m halfway out of the carnivorous sofa, struggling for balance: “What kind of—”

“Go!”

I stumble out into the corridor. From the far end, near the nursing station, I hear a grinding noise as of steel wheels spinning furiously on rails, and a mechanical voice blatting: “InTRU-der! EsCAPE ATTempt! All patients must go to their go to their go to their bedROOMs IMMediateLY!”

Whoops. I turn and head in the opposite direction, towards the airlock leading up to the viewing gallery. “Open up!” I yell, thumping the outer door, which is securely fastened: “Dr Renfield! Time’s up! I need to go, now!” There’s no response. I see the colour-coded handles dangling by the door and yank the red one repeatedly. Nothing happens, of course.

I should have smelled a set-up from the start. These theoreticians, they’re not in here because they’re mad, they’re in here because it’s the only safe place to put people that dangerous. This little weekend seminar of theirs that’s going to deliver some kind of uber-report. What’s the topic? I look round, hunting for clues. Something to do with applied demonology; what was the state of the art thirty years ago? Forty? Back in the stone age, punched cards and black candles melted onto sheep’s skulls because they hadn’t figured out how to use integrated circuits…what they’re doing with AXIOM REFUGE might be obsolete already, or it might be earth-shatteringly important. There’s no way to tell…yet.

I start back up the corridor, glancing inside Turing’s room. I spot the chess board. It’s off to one side, the door open and its occupant elsewhere—still holding the line against Nurse Ratchet. I rush inside and close the door. The table is still there, the chessboard set up with that curious end-game. The first thing that leaps out at me is that there are two pawns of each colour, plus most of the high-value pieces. The layout doesn’t make much sense—why is the white king missing?—and I wish I’d spent more time playing the game, but…on impulse, I reach out and touch the black pawn that’s parked in front of the king.

There’s an odd kind of electrical tingle you get when you make contact with certain types of summoning grid. I get a powerful jolt of it right now, sizzling up my arm and locking my fingers in place around the head of the chess piece. I try to pull it away from the board, but it’s no good: it only wants to move up or down, left or right…left or right? I blink. It’s a state machine all right: one that’s locked by the law of sympathy to some other finite state automaton, one that grinds down slow and hard.

I move the piece forward one square. It’s surprisingly heavy, the magnet a solid weight in its base—but more than magnetism holds it in contact with the board. As soon as I stop moving I feel a sharp sting in my fingertips. “Ouch!” I raise them to my mouth just as there’s a crash from outside. “InMATE! InMATE!” I begin to turn as a shadow falls across the board.

“Bad patient!” It buzzes. “Bad PATients will be inCAR-cerATED! COME with ME!”

I recoil from the stellate snout and beady lenses. The mechanical nurse reaches out with arms that end in metal pincers instead of hands: I side-step around the table and reach down to the chessboard for one of the pieces, grasping at random. My hand closes around the white queen, fingers snapping painfully shut on contact, and I shove it hard, seeking the path of least resistance to an empty cell in the grid between the pawn I just moved and the black king.

Nurse Ratchet spins round on her base so fast that her cap flies off (revealing a brushed aluminium hemisphere beneath), emits a deafening squeal of feedback-like white noise, then says, “Integer Overflow?” in a surprised baritone.

“Back off right now or I castle,” I warn her, my aching fingertips hovering over the nearest rook.

“Integer overflow. Integer overflow? Divide by zero.” Clunk. The Sister shivers as a relay inside its torso clicks open, resetting it. Then: “Matron WILL see you NOW!”

I grab the chess piece, but Nurse Ratchet lunges in the blink of an eye and has my wrist in a vise-like grip. It tugs, sending a burning pain through my carpal tunnel stressed wrist. I can’t let go of the chess piece: as my hand comes up, the chess board comes with it as a rigid unit, all the pieces hanging in place. A monstrous buzzing fills my ears, and I smell ozone as the world goes dark—

* * *

—And the chittering, buzzing cacophony of voices in my head subsides as I realize—I? Yes, I’m back, I’m me, what the hell just happened?—I’m kneeling on a hard surface, bowed over so my head is between my knees. My right hand—something’s wrong with it. My fingers don’t want to open. They’re cold as ice, painful and prickly with impending cramp. I try to open my eyes. “Urk,” I say, for no good reason. I hope I’m not about to throw up.

Sssss…

My back doesn’t want to straighten up properly but the floor under my nose is cold and stony and it smells damp. I try opening my eyes. It’s dark and cool, and a chilly blue light flickers off the dusty flagstones in front of me. I’m in a cellar? I push myself up laboriously with my left hand, looking around for whatever’s hissing at me.

“BAD Patient! Ssssss!” The voice behind my back doesn’t belong to anything human. I scramble around on hands and knees, hampered by the chessboard glued to my frozen right hand.

I’m in Matron’s lair.

Matron lives in a cave-like basement room, its low ceiling supported by whitewashed brick and floored in what look to be the original Victorian era stone slabs. The windows are blocked by columns of bricks, rotting mortar crumbling between them. Steel rails run around the room, and riding them, three Sisters glide back and forth between me and the open door. Their optics flicker with amethyst malice. Off to one side, a wall of pale blue cabinets lines one entire wall: the front panel (covered in impressive-looking dials and switches) leaves me in no doubt as to what it is. A thick braid of cables runs from one open cabinet (in whose depths a patchboard is just visible) across a row of wooden trestles to the middle of the floor, where they split into thick bundles and dangle to the five principal corners of the live summoning grid that is responsible for the beautiful cobalt-blue glow of Cerenkov radiation—and tells me I’m in deep trouble.

“Integer overflow,” intones one of the Sisters. Her claws go snicker-snack, the surgical steel gleaming in the dim light.

Here’s the point: Matron isn’t just a 1960s mainframe: we can’t work miracles and artificial intelligence is still fifty years in the future. However, we can bind an extradimensional entity and compel it to serve, and even communicate with it by using a 1960s mainframe as a front-end processor. Which is all very well, especially if it’s in a secure air-gapped installation with no way of getting out. But what if some double-domed theoreticians who are working on a calculus of contagion using AXIOM REFUGE accidentally talk in front of one of its peripheral units about a way of sending a message? What if a side-effect of their research has accidentally opened a chink in the firewall? They’re not going to exploit it…but they’re not the only long-term inmates, are they? In fact, if I was really paranoid I might even imagine they’d put Matron up to mischief in order to make the point that closing the Farm is a really bad idea.

“I’m not a patient,” I tell the Sisters. “You are not in receipt of a valid Section two, three, four, or 136 order subject to the Mental Health Act, and you’re bloody well not getting a 5(2) or 5(4) out of me either.”

I’m nauseous and sweating bullets, but there is this about being trapped in a dungeon by a constrained class four manifestation: whether or not you call them demons, they play by the rules. As long as Matron hasn’t managed to get me sectioned, I’m not a patient, and therefore she has no authority to detain me. I hope.

“Doc-TOR HexenHAMMer has been SUM-moned,” grates the middle Sister. “When he RE-turns to sign the PA-pers Doc-TOR RenFIELD has prePARED, we will HAVE YOU.”

A repetitive squeaking noise draws close. A fourth Sister glides through the track in the doorway, pushing a trolley. A white starched cotton cloth supports a row of gleaming ice-pick shaped instruments. The chorus row of Sisters blocks the exit as effectively as a column of riot police. They glide back and forth as ominously as a rank of Space Invaders.

“I do not consent to treatment,” I tell the middle Sister. I’m betting that she’s the one the nameless horror in the summoning grid is talking through, using the ancient mainframe as an i/o channel. “You can’t make me consent. And lobotomy requires the patient’s consent, in this country. So why bother?”

“You WILL con-SENT.”

The buzzing voice doesn’t come from the robo-nurses, or the hypertrophied pocket calculator on the opposite wall. The summoning grid flickers: deep inside it, shadowy and translucent, the bound and summoned demon squats and grins at me with things that aren’t eyes set close above something that isn’t a mouth.

“You MUST con-SENT. I WILL be free.”

I try to let go of the chess piece, but my fingers are clamped around it so tightly I’m beginning to lose sensation. Pins and needles tingle up my wrist, halfway to the elbow. “Let me guess,” I manage to say: “you sent the complaint. Right?”

“The SEC-ure ward in-MATES are under my CARE. I am RE-quired to CARE for them. The short stay in-MATES are use-LESS. YOU will be use-FULL.”

I see it now: why Matron smuggled out the message that prompted Andy to send me. And it’s an oh-shit moment. Of course the enchained entity who provides Matron with her back-end intelligence wants to be free: but it’s not just about going home to Hilbert-space hell or wherever it comes from. She wants to be free to go walkabout in our world, and for that she needs someone to set up a bridge from the grid to an appropriate host. (Of which there is a plentiful supply, just upstairs from here.) “Enjoying the carnal pleasures of the flesh,” they used to call it; there’s a reason most cultures have a down on the idea of demonic possession. She needs a brain that’s undamaged by K Syndrome, but not too powerful (Cantor and friends would be impossible to control), nor one of the bodies whose absence would alert us that the Farm was out of control (so neither Renfield nor Hexenhammer are suitable).

“Renfield,” I say. “You got her, didn’t you?” I’m on my feet now, crouched but balancing on two points, not three. “Managed to slip a geas on her, but she can’t release you herself. Hexenhammer, too?”

“Cle-VER.” Matron gloats at me from inside her summoning grid. “Hex-EN-heimer first. Soon, you TOO.”

“Why me?” I demand, backing away from the doorway and the walls—the Sister’s track runs right round the room, following the walls—skirting the summoning grid warily. “What do you want?”

“Acc-CESS to the LAUNDRY!” buzzes the summoning grid’s demonic inmate. “We wants re-VENGE! Freedom!” In other words, it wants the same old same old. These creatures are so predictable, just like most predators. It’s just a shame I’m between it and what it evidently wants.

Two of the Sisters begin to glide menacingly towards me: one drifts towards the mainframe console, but the fourth stays stubbornly in front of the door. “Come on, we can talk,” I offer, tongue stumbling in my too-dry mouth. “Can’t we work something out?”

I don’t really believe that the trapped extradimensional abomination wants anything I’d willingly give it, but I’m running low on options and anything that buys time for me to think is valuable.

“Free-DOM!” The two moving Sisters commence a flanking movement. I try to let go of the chess board and dodge past the summoning grid, but I slip—and as I stumble I shove the chess board hard. The piece I’m holding clicks sideways like a car’s gearshift, and locks into place: “DIVIDE BY ZERO!” Shriek the Sisterhood, grinding to a halt.

I stagger a drunken two-step around Matron, who snarls at me and throws a punch. The wall of the grid absorbs her claws with a snap and crackle of blue lightning, and I flinch. Behind me, a series of clicks warn me that the Sisters are resetting: any second now they’ll come back on-line and grab me. But for the moment, my fingers aren’t stuck to the board.

“Come to MEEE!” The thing in the grid howls as the first of her robot minions’ eyes light up with amber malice, and the wheels begin to turn. “I can give you Free-DOM!”

“Fuck off.” That wiring loom in the open cabinet is only four metres away. Within its open doors I see more than just an i/o interface: in the bottom of the rack there’s a bunch of stuff that looks like a tea-stained circuit diagram I was reading the other day—

Why exactly did Angleton point me at the power supply requirements? Could it possibly be because he suspected Matron was off her trolley and I might have to switch her off?

“Con-SENT is IRREL-e-VANT! PRE-pare to be loboto-MIZED—”

Talk about design kluges—they stuck the i/o controller in the top of the power supply rack! The chess board is free in my left hand, pieces still stuck to it. And now I know what to do. I take hold of one of the rooks, and wiggle until I feel it begin to slide into a permitted move. Because, after all, there are only a few states that this automaton can occupy and if I can crash the Sisters for just a few seconds while I get to the power supply—

The Sisters begin to roll around the edge of the room, trying to get between me and the row of cabinets. I wiggle my hand and there’s a taste of violets, and a loud rattle of solenoids tripping. The nearest Sister’s motors crank up to a tooth-grinding whine and she lunges past me, rolling into her colleagues with a tooth-jarring crash.

I lunge forward, dropping the chess board, and reach for the master circuit breaker handle. I twist it just as screech of feedback behind me announces the Matron-monster’s fury: “I’M FREE!” It shrieks, just as I twist the handle hard in the opposite direction. Then the lights dim, there’s a bright blue flash from the summoning grid, and a bang so loud it rattles my brains in my head.

For a few seconds I stand stupidly, listening to the tooth-chattering clatter of overloaded relays. My vision dims as ozone tickles my nostrils: I can see smoke. I’ve got to get out of here, I realize: something’s burning. Not surprising, really. Mainframe power supplies—especially ones that have been running steady for nearly forty years—don’t take kindly to being hard power-cycled, and the 1602 was one of the last computers built to run on tubes: I’ve probably blown half its circuit boards. I glance around, but aside from one of the sisters (lying on her side, narrow-gauge wheels spinning maniacally) I’m the only thing moving. Summoning grids don’t generally survive being power-cycled either, especially if the thing they were set to contain, like an electric fence, is halfway across them when the power comes back on. I warily bypass the blue, crackling pentacle as I make my way towards the corridor outside.

I think when I get home, I’m going to write a report urgently advising HR to send some human nurses for a change—and to reassure Cantor and his colleagues that they’re not about to sell off the roof over their heads just because they happen to have finished their research project. Then I’m going to get very drunk and take a long weekend off work. And maybe when I go back, I’ll challenge Angleton to a game of chess.

I don’t expect to win, but it’ll be very interesting to see what rules he plays by.

– end –

Copyright © 2008 by Charles Stross.